Dr. Francois Seneca is a Senior Scientist at Centre Scientifique de Monaco. He is a native of Monaco, and studied coral reefs around the world for almost 18 years before returning to work at CSM.

Seneca completed his Bachelors of Science at the University of Hawaii from 2001 – 2004. He wrote his senior thesis on abnormal growths on corals, advised by Dr. John Stimson, who was his coral reef ecology professor. His senior project, on which the thesis was based, was conducted here at HIMB.

After his undergraduate studies, Seneca returned to Monaco for an internship at CSM before attending James Cook University in Australia for his PhD in biochemistry and molecular biology. Following that, he held a post-doc position at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey Bay, California, USA where his work focused on the effects of climate change on corals. Next, he took a post-doc positions at UH’s Kewalo Marine Lab and finally at the Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce in Florida, USA.

Now, as a Senior Scientist at CSM he is working on the development of the Aiptasia sea anemone as a model for host-pathogen interactions from corals to humans.

If you are interested in Francois’ work you can fseneca@centrescientifique.mc

During this mission in Hawaii, we are focused on collecting samples particularly from two species of tropical Scleractinian (stony) corals that show abnormal growths:

- Porites evermanni (common name lobe corals) (massive)

- Porites compressa (common name finger corals) (branching)

Stony corals are the world’s primary reef builders. Reef building corals are only found in shallow, tropical and sub-tropical waters because the algae that they are in symbiosis with need light for photosynthesis and temperatures ranging from 70-85 degrees Fahrenheit.

Reefs play a crucial role in protecting shorelines from storms and surge water and help prevent shore erosion. Reefs are vital to the global economy with an estimated value of 172 billion US Dollars annually providing food, protection, tourism jobs and shoreline protection.

Hawaii does not have many coral species and only five species here are main reef builders. Because of this, and because coral health is imperative to marine life, understanding why these corals are showing abnormal growths, and how they are fighting the disease (or not) is incredibly important.

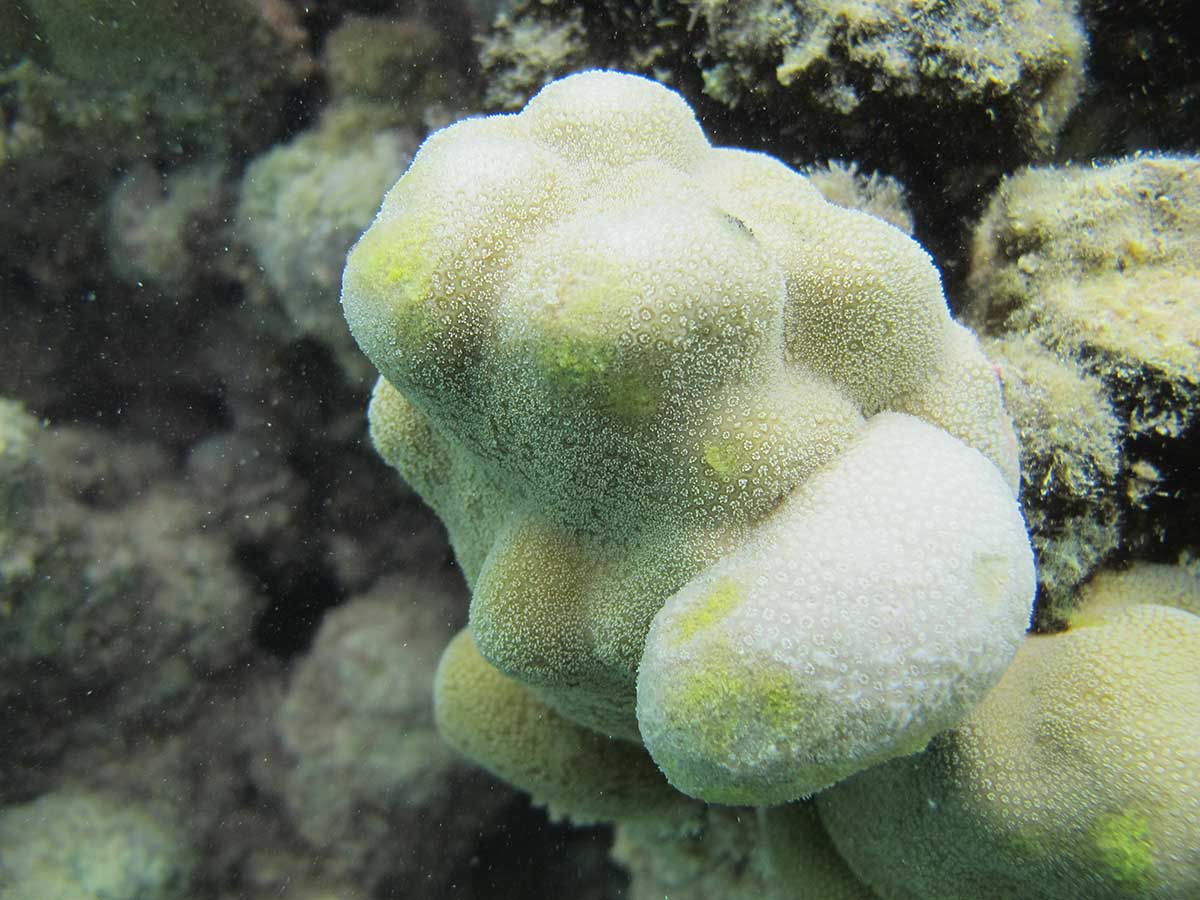

The growths (abnormal cell reproduction) look different on the two species.

On the Porites evermanni there is a pink pigment that is produced by the coral as a protection of something that is invasive. We see the pigment coming later (not in the initial growth). This reaction tells us the coral is fighting something invasive.

On the Porites compressa, the growths are clearly distinguishable from the healthy coral as shown in the photo below. The P. compressa is a braching coral, meaning it grows in finger like shapes, but when the abnormal growths are present, they grow in massive formations, making it easy to see the disease.

The International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) Secretariat, which began in 2004, has always been co-chaired by a developed and a developing country. Since July 1st, 2018 and ending June 30th, 2019, this initiative is hosted by Monaco, and co-chaired alongside Australia and Indonesia until mid-2020. The handover ceremony took place in Paris on July 4th. The ICRI Secretariat is hosted by members who volunteer for spots without exception every two years. It organizes its work through Action Plans approved by existing members, and the next General Meeting, and the first one under the Monaco host, will happen in December 2018. A workshop will take place on December 4th, to provide “innovative funding for coral reefs”.

The ICRI, International Coral Reef Initiative, is a relaxed partnership among nations, international organizations, and non-government organizations, which help protect coral reefs globally and established itself in 1994. The intention of the ICRI is to raise global awareness around the extremities of coral reefs around the world, and to promote best practices and re-building of such coral reefs.

For more information visit ICRI Forum.

UNESCO PR

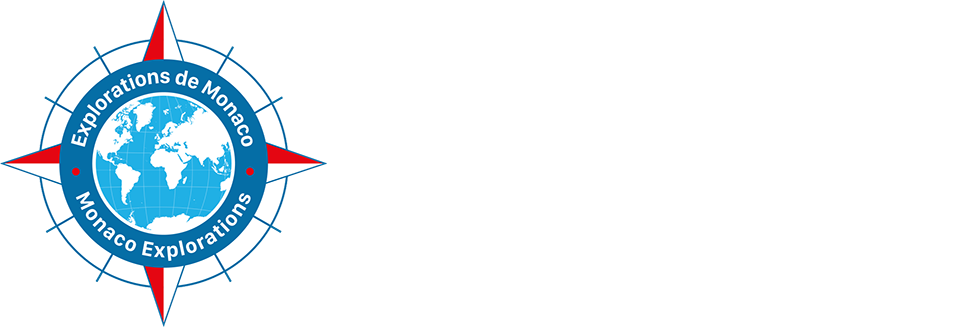

The World Heritage Committee, meeting in Manama since 24 June, decided Tuesday to remove the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System from the List of World Heritage in Danger.

The Committee considered that safeguarding measures taken by the country, notably the introduction of a moratorium on oil exploration in the entire maritime zone of Belize and the strengthening of forestry regulations allowing for better protection of mangroves, warranted the removal of the site from the World Heritage List in Danger.

The site was inscribed on the List in Danger in 2009 due to the destruction of mangroves and marine ecosystems, offshore oil extraction, and the development of non-sustainable building projects.

The Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1996, is an outstanding natural system consisting of the largest barrier reef in the northern hemisphere, offshore atolls, several hundred sand cays, mangrove forests, coastal lagoons and estuaries. The system’s seven sites illustrate the evolutionary history of reef development and are a significant habitat for threatened species, including the marine turtle, the manatee and the American marine crocodile.

The Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1996, is an outstanding natural system consisting of the largest barrier reef in the northern hemisphere, offshore atolls, several hundred sand cays, mangrove forests, coastal lagoons and estuaries. The system’s seven sites illustrate the evolutionary history of reef development and are a significant habitat for threatened species, including the marine turtle, the manatee and the American marine crocodile.

The List of World Heritage in Danger is designed to inform the international community of conditions threatening the very characteristics that warranted the inscription of a property on the World Heritage List and encourage corrective measures.

The 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee continues until 4 July.

Diseased corals are the research target for our next mission in Hawaii, conducted in collaboration with Centre Scientifique de Monaco (CSM) and TARA Expeditions Foundation.

CSM will study diseased corals in Hawaii from June 15-25, 2018.

In past decades scientists have observed drastic increases of coral disease, showcasing the negative effects fo climate change and ocean acidification on the health of marine ecosystems. Unfortunately, the close connection between the future of the oceans and climate leads us to expect that diseases affecting the reefs will continue to increase. Studying these major changes in marine ecosystems has been the driving force for the collaboration between HSH Prince Albert II and the Tara Expedition Foundation since 2009 and more recently with the launch of Monaco Explorations in 2017.

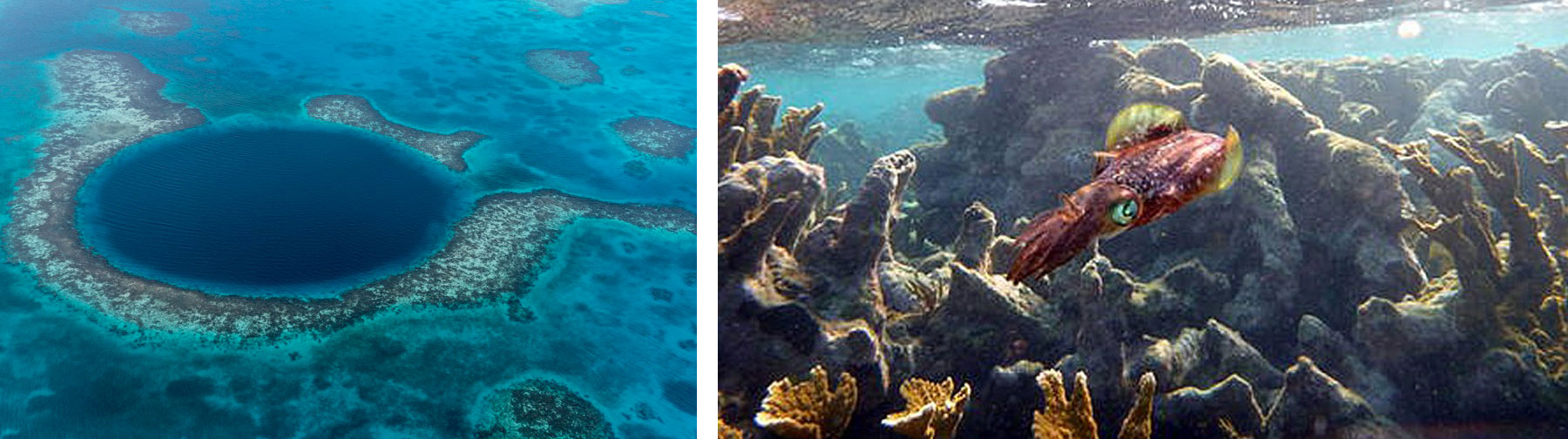

With experts in how tropical, Mediterranean and deep coral reefs function, the Scientific Center of Monaco has been a partner of the Tara Pacific Expedition 2016-18. In Hawaii, the CSM team will take advantage of the visit of the Tara in Kaneohe Bay, to conduct field work focusing on coral abnormal growth for the Monaco Explorations in collaboration with the Hawaiian Institute of Marine Biology of the University of Hawaii.

From the 15thto the 25thof June, the CSM team will concentrate their work on “tumors” found on corals, a phenomenon with poorly understood origins that affects more that 40 species of Scleractinian corals in the Indo-Pacific and Caribbean regions. This disease is characterized by an abnormal growth on a distinct area of the colony. Although the growths are known by some scientists as “tumors”, their malignancy remains to be determined. Yet, the origin of this disease may involve the bacteria living on the abnormal tissues.

From coral to human health

Similar to classical model organisms, these “tumors” represent a unique opportunity for multiple studies that would enrich our knowledge of coral biology, as well as coral innate immunity, which shows close similarities to humans. In fact, studying diseases to understand how healthy organisms function was the central tenant of experimental medicine practiced in the middle of the 19thcentury by Claude Bernard, the father of modern medicine. The CSM researchers will apply the same approach to understand corals today.

Beyond the importance of this project to the future of coral reefs, this work will also help us better forecast future biomedical or biological problems, such as the links between diseases and the interactions of host-pathogens. Thanks to its double capacity in coral and medical biology, the CSM is a unique laboratory possessing the expertise to study these abnormal growths from the colony to the gene.

Some samples from healthy and affected coral colonies will be immediately processed to extract molecules of interest in the laboratory of the Hawaiian Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB), before being shipped to Monaco. Others samples will be quarantined and shipped live to Monaco to be kept under controlled conditions in the laboratory. In total 120 samples will be collected from the three main reef-building coral species in Hawaii: Porites lobata, P. compressa, and Montipora capitata.

Monaco will co-chair the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) in July 2018

As 2018 was announced the International Year of the Coral Reefs, this mission conducted by the CSM as part of the Monaco Explorations in collaboration with Tara and the FPA2, constitutes also the first contribution of the Principality of Monaco as co-chair of the ICRI. ICRI was founded in 1994, with the goal to internationally promote knowledge and solutions allowing the preservation of coral reefs and associated ecosystems. From July 2018 until 2020, Monaco, Australia and Indonesia will co-chair the organization. One of the goals to meet in 2020 is to produce a global report on the state of these ecosystems of considerable ecological and socio-economical importance.