Dr. Francois Seneca is a Senior Scientist at Centre Scientifique de Monaco. He is a native of Monaco, and studied coral reefs around the world for almost 18 years before returning to work at CSM.

Seneca completed his Bachelors of Science at the University of Hawaii from 2001 – 2004. He wrote his senior thesis on abnormal growths on corals, advised by Dr. John Stimson, who was his coral reef ecology professor. His senior project, on which the thesis was based, was conducted here at HIMB.

After his undergraduate studies, Seneca returned to Monaco for an internship at CSM before attending James Cook University in Australia for his PhD in biochemistry and molecular biology. Following that, he held a post-doc position at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey Bay, California, USA where his work focused on the effects of climate change on corals. Next, he took a post-doc positions at UH’s Kewalo Marine Lab and finally at the Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce in Florida, USA.

Now, as a Senior Scientist at CSM he is working on the development of the Aiptasia sea anemone as a model for host-pathogen interactions from corals to humans.

If you are interested in Francois’ work you can fseneca@centrescientifique.mc

During this mission in Hawaii, we are focused on collecting samples particularly from two species of tropical Scleractinian (stony) corals that show abnormal growths:

- Porites evermanni (common name lobe corals) (massive)

- Porites compressa (common name finger corals) (branching)

Stony corals are the world’s primary reef builders. Reef building corals are only found in shallow, tropical and sub-tropical waters because the algae that they are in symbiosis with need light for photosynthesis and temperatures ranging from 70-85 degrees Fahrenheit.

Reefs play a crucial role in protecting shorelines from storms and surge water and help prevent shore erosion. Reefs are vital to the global economy with an estimated value of 172 billion US Dollars annually providing food, protection, tourism jobs and shoreline protection.

Hawaii does not have many coral species and only five species here are main reef builders. Because of this, and because coral health is imperative to marine life, understanding why these corals are showing abnormal growths, and how they are fighting the disease (or not) is incredibly important.

The growths (abnormal cell reproduction) look different on the two species.

On the Porites evermanni there is a pink pigment that is produced by the coral as a protection of something that is invasive. We see the pigment coming later (not in the initial growth). This reaction tells us the coral is fighting something invasive.

On the Porites compressa, the growths are clearly distinguishable from the healthy coral as shown in the photo below. The P. compressa is a braching coral, meaning it grows in finger like shapes, but when the abnormal growths are present, they grow in massive formations, making it easy to see the disease.

After collecting samples of diseased corals from the sea, Drs. Dorota Czerucka and Francois Seneca must preserve the samples in various forms to ship the samples to their lab and perform their research.

We are hosted by the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology and able to use their laboratories here on Moku O Loʻe Island to preserve the samples.

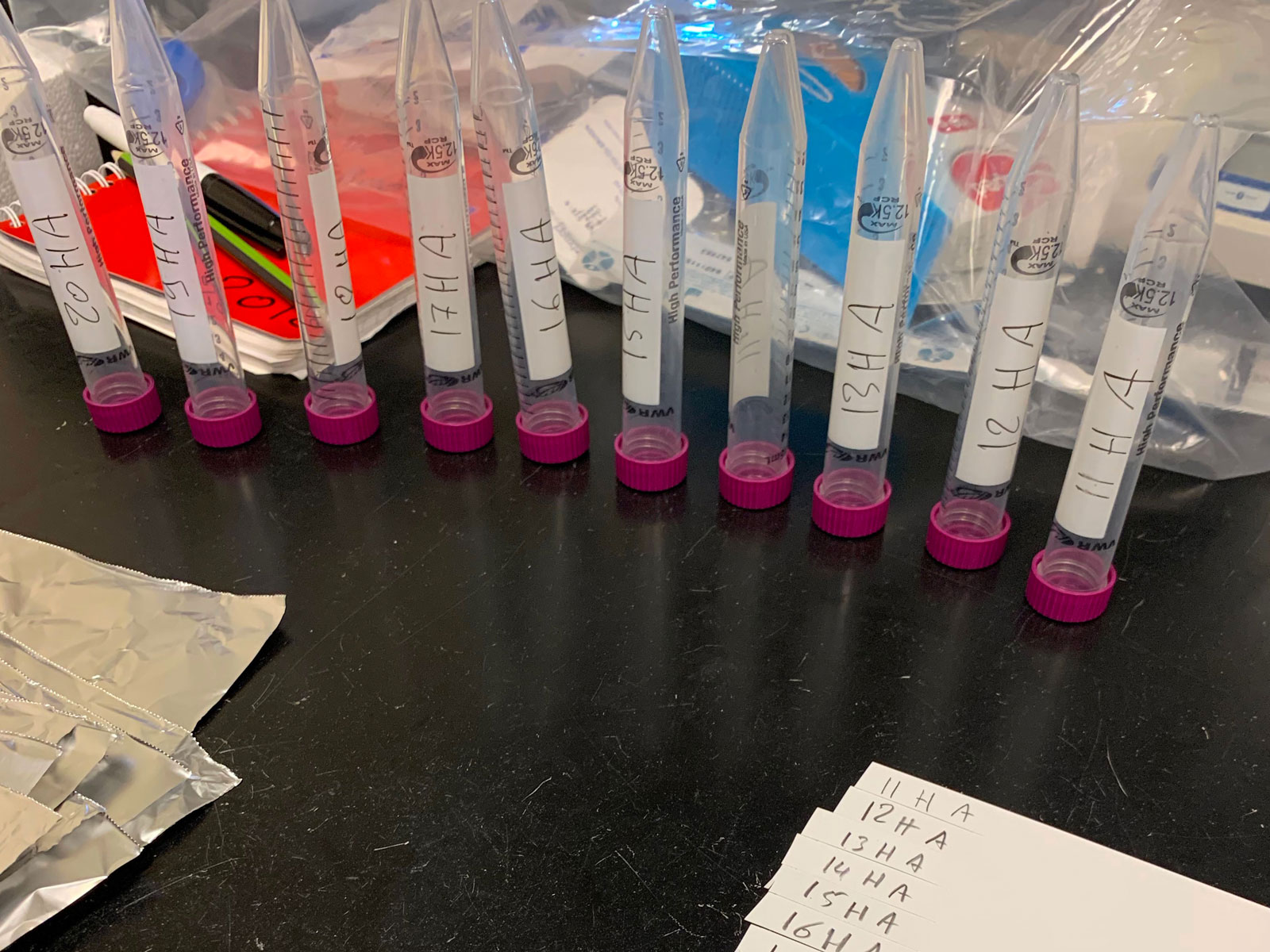

First, we use underwater paper to mark each sample, 1-10 healthy, and 1-10 with tumors.

Next, prepare the liquid nitrogen. This is one way the samples are preserved. Dropping them in the -196 degree liquid nitrogen preserves the sample exactly as it was found, so that DNA, RNA and proteins can be extracted and analyzed based on the environment in which the sample is living. The sample is cut into smaller pieces as we will preserve it multiple ways – the nitrogen is one, but we also keep some alive in sea water to transport them back to our lab in Monaco and let them continue to grow.

Next we move on to the wet lab where there is sea water pumped into tables so the samples can continue to live. First step here is to prepare these stems marked with the sample number and either H for healthy or T for tumor. The stems are placed into a tray, as shown in the photo, with the diseased coral on the left and the healthy on the right. Each sample is cut into 3 so there are more chances of a live coral being preserved, and because each will be used for a different research purpose. When we are ready to leave Hawaii, the samples are suspended on a string and floated in a bag filled with seawater and 100% oxygen, which is what they will consume to survive on their trip to Monaco.

While collecting pieces of coral, we also scrape the mucus from their surface to collect and analyze bacterial communities. Here you can see that it’s much like the coral – there is one sample of mucus taken from healthy coral and one taken from the diseased coral on the same colony. The samples are mixed with the Vortex machine which ensures the bacteria is completely mixed with the sea water, then put into centrifuge to separate the bacteria completely before preserving it in the liquid nitrogen and preparing it for shipping back to Monaco. In the photos it is easy to see the difference between the healthy mucus (clear) and the diseased mucus (brown).

To collect samples for research, the scientists must spend time in the sea searching for coral colonies that show abnormal growths. Each day, we suit up and collect our materials and head out to sea with snorkels and masks hoping to collect samples from a total of ten colonies. When one is identified, a photo is taken to document the size and GPS coordinates. Next, Francois Seneca chips away 2 pieces from the colony – one of the healthy coral and one of the diseased coral. He then stores the samples in separate bags pre labeled 1-10 for both healthy and diseased samples. Next, he repeats the process with a new colony.

Here’s a video that shows what that process looks like.

Our mission here in Hawaii is in collaboration with Drs. Dorota Czerucka and Francois Seneca from Centre Scientifique de Monaco (CSM). This team is working on a project on the development of the Aiptasia sea anemone as a model for host pathogen interactions from corals to humans. Part of this process is to collect samples from coral colonies here in Hawaii that are showing abnormal growths and attempt to understand why the growths are occurring and how the corals are reacting to and fighting the growths. In doing so, because of similarities in innate immunity in humans, it is also possible to apply this research to human health and immunity.

Collecting the samples is fairly simple, albeit tedious, work and the biggest challenge in this part of the research process is ensuring the samples are preserved correctly for a safe and healthy return to the laboratory in Monaco. The photo below shows an example of a coral with an abnormal growth (the top part).

On this mission, we are very fortunate to be hosted by the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology. (HIMB)The institute is owned and operated by the University of Hawaii and is located on the small private island of Moku O Loʻe, also known as Coconut Island. The island has a rich and interesting history, which you can read about on the HIMB website. To get to the island, you must have permission and a sponsor from the University, and show documentation of such to the ferry boat operator who transfers you from the pier to the island.

We arrived late in the afternoon and had just enough time to put our things away and walk around to explore before catching the ferry back to town for dinner. Tomorrow we begin collecting coral samples.

Today our teams arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii for our next mission. While here, a team from Centre Scientifique de Monaco (CSM) will be collecting diseased coral samples and preserving them to take back to their laboratory in Monaco for continued research. Before that work starts, and while the team prepares their fieldwork equipment, the rest of us take advantage of exploring just a couple of the sights this beautiful island has to offer. Even the views of Hawaii from the air are amazing!

We began our day with a walk on Waikiki Beach, one of the world’s best-known beaches, and it’s easy to see why. From here we could see Diamond Head State Monument and decided we had to visit.

Diamond Head (Lēʻahi) is a crater, which you can hike to the top of via a 1.8km trail that is scaled with numerous switchbacks. The crater is believed to have been formed 300,000 years ago from a single volcanic eruption. The views from the trail and the peak are incredible.

After our hike to the peak of Diamond Head we set out to discover a seaside view in a local neighborhood where the views were sure to be different from the shores of Waikiki Beach, and luckily we found a little pathway between two houses and took a few photos of the area.

Finally, our last stop before going to meet the scientists at the work site, we found a local lunch treasure, Mikeʻs Huli Chicken roadside food truck! (Huli Huli means “turn turn”). The chicken and shrimp were delicious and the staff was friendly and helpful, we highly recommend this Hawaiian gem.

While we were out having a little island adventure, Drs. Dorota Czerucka and Francois Seneca from CSM were on their way to Moku O Loʻe Island in the Kāneʻohe Bay where we will be stationed for this mission.